Animals in Medicine: The Ethics of Animal Harvesting for Medicinal Purposes

Getty Images/Dorling Kindersley

The Greek Myth, Daedalus and Icarus, is one of the first recorded instances of xenotransplantation.

January 13, 2023

With the increased debate discussing the ethicality of xenotransplantation: the process of transplanting organs between members of different species, you would probably think this is a new scientific revelation. However, around 40 B.C.E in the Greek myth, Daedalus and Icarus, a father created wings for his son- the first known occurrence. Animals have also been used in traditional medicine since at least 500 B.C.E. Although having existed for such a long time, the question of whether animals should be harvested for such medicinal purposes still remains unanswered.

Would you refuse treatment if you knew it was made from an animal byproduct or came at the cost of an animal’s life? No matter your answer, they are still widely utilized today for both modern and traditional medicine.

Why is there still a debate?

A primary reason why the ethicality of animal harvesting for medicinal purposes remains questionable is due to various personal beliefs. Many medical products that are commonly used to treat illness and infections are of animal origin. Clearly, this is problematic for those who follow a religion, have moral commitments, or dietary restrictions that prohibit the ingestion of animals.

A pillar of the world’s major religions are animals and the role they play differs between them. Many Christians believe that animals were created by God to serve man, while others believe animals are sentient and deserve to be treated with respect. In Hinduism, animals are sacrificed in religious ceremonies, but the way they are treated leading up to the sacrifice is still a crucial part. In India where 80% is Hindu, the act of killing cows is banned due to their sacredness so they do not eat any beef products. The Qur’an explicitly states that animals can be used by humans if slaughtered by strict guidelines, but animal cruelty is considered a sin. Judaism teaches that it is only okay to kill animals if for essential human needs.

Clearly, these major world religions entirely advocate for the righteous treatment of animals- something that is not taken into consideration with zootherapy or xenotransplantation. None of the animals harmed for medicinal purposes are killed by halal or kosher standards which makes them unsuitable for Muslims and Jewish people.

Additionally, vegan and vegetarian lifestyles are widely adopted as a result of popular culture health trends. This results in many religious or dieting patients forced to deny treatment even when animal-derived alternatives are longer-lasting, cheaper, or safer.

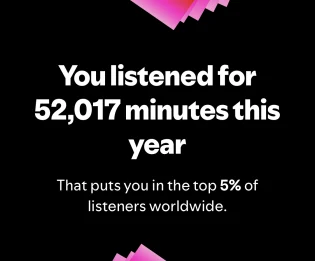

However, animal medicine is a rooted value in culture whether that be a result of inaccessibility or a generational practice with historical origins. Long before new technologies existed in order to develop various synthetic drugs, naturally derived plants and animals were being used as treatment for various illnesses. The World Health Organization estimates 80% of the world’s population relies on animal-based medicines.

In their research, Vats & Thomas argue the significance of animals for Tanzanians. Their use of animals dates back to the pre-colonial era when colonialists enabled the development of African sciences. As a result of perseverance, tribes developed medicines from naturally occuring healers- animals. This story is not only true for Africa, but communities across the globe.

While not a traditional medicine, in several countries, there are cultural barriers to human organ donation, e.g, Japan, and yet there are none to xenotransplantation. Taking away the possibility of animal organ donation in areas would hurt the medical business and be fatal for those who require treatment, but are restricted from utilizing human parts. On one hand, it is valid to think zootherapy is unethical due to religions opposing animal use or cruelty for human means. On the other hand, it is still true that the inhumane use of animals cannot simply be outlawed when it is such a crucial part of people’s lives and history.

Dangers: from mental to physical

Xenotransplantation is a promising field, but that does not discount the dangers that follow. Although not new, its physical and mental uncertainties remain a concern. Though some argue its advantages outweigh the concerns and medicine must continue moving forward for human benefit. Scientists began to dive into donor modification to make the donor and host similar before beginning the transplant. This added step hopes to alleviate complications, but this is where the ethical dilemmas begin.

The Young Family by artist Patricia Puccini, illustrates the gray boundary for human and nonhuman. In this sculpture, viewers see a pig and woman mutant; “cast in brown-pink silicone, the color of a textbook pig, with human hair. The body—unclothed, wrinkled, and veined —occupies a disturbingly ambiguous territory between human and animal, youth and age, natural and unnatural.” In her work, Puccini asks the audience to inquire how far technology should interfere with natural life. She hopes it exposes an overlooked aspect scientists conceal; how far is too far when crossing lines of animal and human crossbreeding?

Further, xenotransplantation can hold physical dangers for recipients. Without the genetic modification of animals, the risk of rejection for humans is through the roof. The experimenters list over a dozen potential side effects including diarrhea, vomiting, bacterial disease, hemorrhaging, and rashes. Common sense says that doctors have perfected their craft and fatalities occur infrequently. However, grafting and transplantation are risky procedures even for experienced surgeons. “The lack of deceased human donors has popularized living donor transplants and there have been a number of donor deaths after these procedures,” says David Cooper M.D.

Animal AND human cruelty

Finally, the ethicality of animal harvesting for medicinal purposes is clearly the treatment towards those involved in the procedures. As animal testing precedented, animals used in labs are not treated humanely. This is another motive for patients to reject treatment where animal well-being is a cost. Reportedly at Columbia Medical Center, “baboons were caged alone, subjected to multiple survival surgeries, biopsies, and repeated blood draws. The animals were kept alive for up to 360 days following transplantation and then finally killed.”

Yet, animals aren’t the only party who are subject to mistreatment. Human recipients must pay a price for their life saving care. The 2001 Public Health Service characterized humans as “xenotransplantation product recipients.” Sheila Jasanoff states that this label, “reduced the treated patient to one-dimensional status, as the carrier of a novel, potentially infectious, biomedical product. Stripped of other attributes of personhood, they were to be subjected to perhaps lifelong surveillance, submit to regular monitoring, and make physical movements publicly available”. The cost of this procedure is to become a social outcast and specimen for scientific oversight.

Obviously patients are not kept in a lab or forced to be studied under a microscope as the animals are. Understandably, patients will need to be monitored for complications that may arise due to infection or rejection of the transplant as mentioned previously.

What’s the conclusion and what can we do?

While facts and data are able to support either side, it is impossible to decide whether something is ethical as it is based upon personal belief and experience. However, to satisfy those with restrictions without harming advocates, it is only obvious to address the bigger issue. Many manufacturers and doctors alike have not been transparent about the contents of medicines they prescribe and since we are becoming more conscious of what we consume due to exposure in the news and media, this is becoming a more prominent issue. Actually, according to Joe Darrah, “manufacturers are not required to declare on labels how an ingredient is sourced, which means it is not present in drug databases and clinical decision-support systems for physicians.” As mentioned previously, this poses a threat to those who follow a specific religion or have dietary restrictions that prohibit the ingestion of animal products. Medical professional’s lack of respect and failure to recognize religious concerns continue to be a reason groups steer clear of professional aid- having fatal consequences. Once again, the ethicality of animal harvesting remains debatable, but consequently results of animal-derived medicines have harmed many and infringed on their personal values. What can be done to ensure regard for those opposed to animal harvesting due to personal reasons has yet to be acknowledged.